Doubts and certainties about the aviation of the future

From SAF fuels to hydrogen aircraft

From SAF fuels to hydrogen aircraft

Aviation is an essential means of transport for the Spanish economy, where tourism accounts for more than 12% of GDP and eight out of ten tourists travel by air. To achieve climate neutrality by 2050, this strategic sector is facing a profound transformation that represents a huge technological and economic challenge. In this context, the use of sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) is emerging as the main option for immediately reducing CO2 emissions, together with improving aircraft efficiency. In the medium and long term, other still emerging alternatives, such as hydrogen aircraft or electric propulsion, will be added.

It is a big challenge, but human beings need to keep flying and any one of us could have been one of the passengers on the nearly 7,200 daily flights that took off or landed at a Spanish airport in July 2023, the month in which the highest number of flights in the history of our country was recorded. We need, therefore, to find solutions to be able to fly in a more sustainable way and that these alternatives also allow us to reduce emissions quickly.

An economic and technological challenge

To get an idea of the magnitude of the economic and technological challenge of decarbonizing aviation, there are around 37,100 active aircraft in the world, and more than 15,460 on production order, according to CAPA Fleet Database, the largest database in the sector. The development of a new aircraft model, which can easily cost more than 900 million euros, "takes between 9 and 12 years," explains Abel Jiménez, chief engineer for decarbonization projects at ITP Aero, a Spanish aircraft engine manufacturer. "We are also in a sector where aircraft are in service between 20 and 25 years because they are very high-value assets and these operating periods are needed to amortize them."

The priority is to find new ways to propel aircraft, which is no easy task for aircraft that can weigh up to 300 tons. "The decarbonization of aviation is more complex than that of other means of transport because it is a sector that cannot be electrified and has very rigorous safety certifications. But that doesn't mean it can't be done and, in fact, we are doing it," says Teresa Parejo, Iberia's Director of Sustainability.

"At least for the next twenty years, the main way of propelling aircraft will continue to be the combustion engine" Abel Jimenez, ITP Aero.

The first prototypes of hydrogen-powered aircraft are scheduled to begin flying by the middle of the next decade, and it will be several decades before this technology can replace the thousands of aircraft needed to support the world's air traffic. As for battery-electric propulsion, it will only be applicable to small aircraft, such as light aircraft, small regional jets, and helicopters for smaller routes and loads. With that in mind, "at least for the next twenty years, the main way of propelling aircraft will continue to be the combustion engine," continues Abel Jiménez, of ITP Aero.

Therefore, there is a broad consensus in the industry that Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAF), which emit up to 80% less CO2 than conventional kerosene, are the best tool to decarbonize aviation. In addition to reducing emissions, SAF has another significant advantage: "it can be used in the combustion engines of current aircraft without any modification and also does not require investment to create a supply infrastructure different from the one we already have, which is highly leveraged and very strict for safety reasons. This is very important because aviation is a global issue: the systems used in Barajas are the same ones that will have to be used in airports in Singapore or Mexico City," explains Francisco Lucas, Senior Manager of Sustainable Aviation at Repsol.

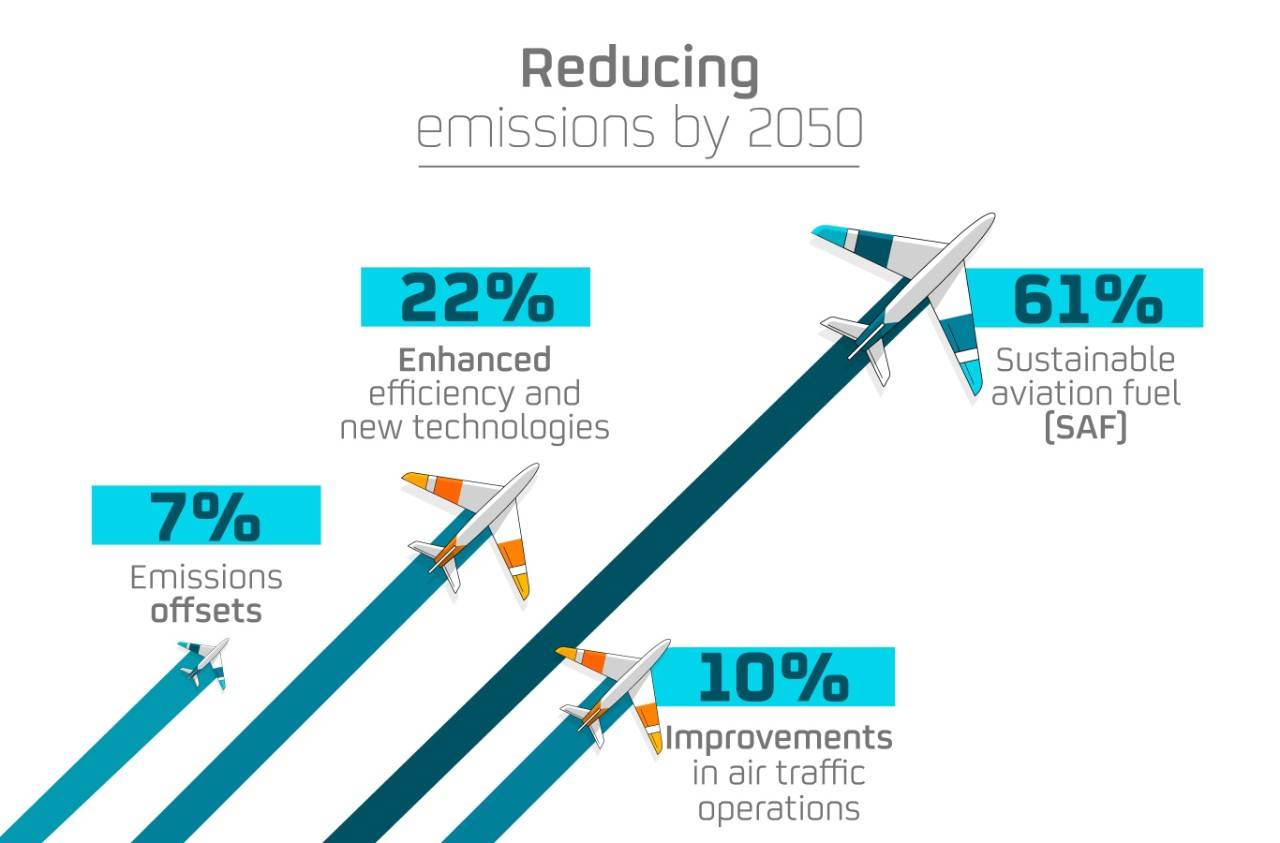

The 'Waypoint 2050' report by ATAG, an international coalition of 40 industry organizations, from aircraft manufacturers to airlines, airports and industry suppliers, predicts that by 2050, UAS will account for 61% of the reduction needed to achieve net zero emissions; another 22% will come from increased aircraft efficiency and the development of technologies such as electric, hybrid, or hydrogen aircraft; 10% from improvements in operation and air traffic management; and a further 7% through emissions offset markets.

SAF fuels, a solution that is already available

SAF fuels, a solution that is already available

The most consistent and impactful way to work towards aviation with a lower carbon footprint is to replace conventional kerosene with these sustainable aviation fuels, which can already be produced using all types of organic waste, such as used cooking oil, agricultural and livestock waste, or residues from the agri-food industry.

In addition, "the promotion of a powerful SAF industry that meets the needs of aviation could represent a historic opportunity for Spain's economy," says Teresa Parejo. A recent study commissioned by Iberia and Vueling to the consultancy firm PwC estimates that up to 270,000 jobs could be created by 2050, with a contribution of 56 billion euros to GDP. This would require the construction of between 30 and 40 plants for the production of this renewable fuel, with an investment of approximately 22 billion euros.

The use of sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) is emerging as the leading option to immediately reduce CO2 emissions.

In Spain, the first plant of this type is being built by Repsol at its industrial complex in Cartagena, with an investment of 200 million euros. It will begin operating at the end of this year and will produce 250,000 tonnes per year of renewable fuels made from organic waste, mainly used cooking oil, most of which will be used to cover the needs of the airline industry.

For companies like Iberia, SAF "are one of the pillars of our decarbonization strategy, and we want 10% of the fuel used by our aircraft in 2030 to be SAF, four points above the EU target for that date," explains Teresa Parejo. The company has already made several flights with these fuels, such as the one linking Madrid with Bilbao in 2021 using a SAF produced by Repsol. A few months later, Iberia would use the same type of fuel to power three flights between the Spanish capital and the U.S. cities of Washington, Dallas, and New York, reducing its emissions by 125 tonnes of CO2.

Lighter and more efficient aircraft

Lighter and more efficient aircraft

The aviation industry will have to continue to implement solutions in other key areas to improve its sustainability. These include improving aircraft design to make them lighter and more efficient, something that has been in the works for decades. "The performance of the new generations of commercial aircraft," says Abel Jiménez, "offers a 15-20% improvement in efficiency over previous generations from the 1990s or early 2000s. And when compared to the aircraft of the 1960s, it is nearly 60% better, largely due to the progress achieved in the engines, but also because of the contributions made to the aircraft's aerodynamics".

For Airbus, " renewing the fleet with lighter and more efficient aircraft contributes to reducing the environmental impact of aviation". Airlines are already making a significant investment effort to acquire these new, more sustainable aircraft, but this renewal also has its limits due to the high cost of each unit. It is also true that "it is becoming more and more technologically challenging to keep increasing aircraft performance. But each 10% improvement we achieve, as we are looking for now with the UltraFan, is vitally important," Jiménez continues.

Improving air traffic, an option with an immediate effect

The high cost of developing new technologies is one of the main obstacles in the process of decarbonizing aviation. For this reason, the sector is also committed to other complementary measures, which have a more immediate effect and, above all, are less costly. One of these is the improvement of air traffic management, which can bring benefits such as reducing the distances traveled by aircraft by using more direct routes between destinations, with subsequent fuel savings.

Under the current system governing air traffic, pilots must fly along predefined airways, inherited from the days when air navigation was guided by radio beacons located at ground stations and established by each national air traffic control authority. As a result, these air routes often involve zigzagging flights, even though current satellite navigation technology now makes it possible to fly along straighter trajectories.

Enaire, the entity that manages Spanish airspace, the fourth largest in Europe in terms of traffic volume, estimates that the work it is already doing to facilitate more direct flights over Spain will save 9.8 million kilometers between 2021 and 2025, which is equivalent to circling the Earth 246 times, and will reduce emissions equivalent to the CO2 that would be absorbed by 9.2 million trees.

But there is still room to reduce flight times. In 2004, the EU initiated the creation of the Single European Sky to overcome the fragmentation of airspace caused by national borders, which hinders more efficient traffic over the continent, one of the most congested in the world. A full development of this unified airspace would bring an average reduction of more than 11 minutes in intra-European flights and savings of between 8% and 10% in CO2 emissions, "a measure that airlines have been demanding for 20 years, but on which the member states have not been able to agree", says Teresa Parejo.

Electric aircraft for urban mobility

Electric aircraft for urban mobility

The first prototypes of electric airplanes will take flight at the end of this decade, with use limited for the time being to short distances. The reason for this is the sheer weight of the batteries: "their energy density is so high that 60 kilograms of today's best batteries are needed to produce the same amount of energy as is contained in 1 kilogram of kerosene. If we consider that an average aircraft carries about 20,000 kilograms of kerosene on board, electric propulsion is unfeasible for large aircraft," continues Abel Jiménez.

Hydrogen aircraft, a long-term alternative

Hydrogen aircraft, a long-term alternative

In the case of hydrogen, Airbus is currently working on three models, which it has named ZEROe, with the aim of bringing the world's first hydrogen-powered commercial aircraft to market by 2035, including the Turbofan, with a capacity to carry about 100 passengers and a range of 1,850 kilometers, enough to fly from Barcelona to Berlin. The first pilot test will take place by the middle of this decade, when Airbus plans to adapt an A380 model -nicknamed Superjumbo- to store four tanks of liquid hydrogen.

Airbus is currently working on three models, with the aim of bringing the world's first hydrogen-powered commercial aircraft to market by 2035.

Experts agree that hydrogen is a technology with great potential for the decarbonization of aviation, although its development still presents significant challenges. "We are therefore talking about the medium to long term because the world flies a lot and the use of hydrogen represents a change in technology whose implementation could transform the entire ecosystem of commercial aviation. But it is an energy vector on which we must undoubtedly continue to work," Lucas concludes.

What is clear is that the sector must undergo a profound transformation in the coming decades to become more sustainable. It has already started to do so and is now working on the development of new technologies to reduce emissions, some in the short term, such as the use of renewable fuels, and others that will take longer, such as the design of new aircraft or the use of hydrogen. All of them should help to achieve a single goal: to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

Repsol and its sustainable fuels plant in Cartagena

In Spain, the first plant of its kind has been launched by Repsol at its Cartagena industrial complex, with an investment of 200 million euros. It will be operational by the end of this year and will produce 250,000 tonnes of 100% renewable fuels per year made from organic waste, mainly used cooking oil, most of which will be used to cover the needs of the airline industry.

For companies like Iberia, SAFs "are one of the pillars of our strategy to reduce carbon emissions, and we want 10% of the fuel used by our aircraft to be SAFs by 2030, four points above the EU target for that date," explains Teresa Parejo.

The company has already made several flights with these fuels, such as the one linking Madrid with Bilbao in 2021 using a SAF produced by Repsol. A few months later, Iberia used the same type of fuel to power three flights between the Spanish capital and the U.S. cities of Washington, Dallas, and New York, reducing its emissions by 125 tonnes of CO2.